‘This book could do best without a review,’ says Maqsoodul Haque in the lead poem of The Bangladesh Poet of Impropriety, ‘Limits of Our Limitations’, and one would tend to agree with him, for the poems all speak for themselves. Loud, resonant, abrasive, pleading, ironic yet consistently to the point, the poems are a record of a poet’s obsessive probing of the ills of our age as well as possibilities that go waste.

In poem after poem, Haque documents with abounding energy the hypocrisy, duplicity and cruelty that characterize our politics and sections of our society, not sparing our so called civil society, the intelligentsia and the Media. Yet equally compulsively and candidly, he details his private moments, his anguish and sorrow, his alienation from everything around him, his revulsion for flattery and doublespeak and the various autobiographical turns the poems take-such as his childhood experiences or his life with his wife till her death in 2004.

The variously lineated verse in unrhymed or playfully rhymed lines with political, literary, musical and televisual allusions renders strong feelings, images and ideas in a continuously gushing stream of words.

One can easily detect Haque’s anguish at the injustice and corruption that have eaten into the moral fabric of our society-he doesn’t mince his words, and prefers to lay everything upfront—but his personal. moments also engage the readers, allowing them to pause and ruminate. If some poems are all fire and brimstone, others are reflective and are full of raw anguish and sadness. Tying together the moods of anger, expectation, consternation and contemplation, the poems, in the end explore both the public world of action (mostly negative), and the private world of reflection and quiet resistance.

Haque is right: the poems are not meant to be reviewed but reflected on, yet a few lines by way of a Foreword may not be out of place. Indeed, it is not everyday that one comes across such a candidly disarming, and at times unsettling, collection of poems that bravely name names, and point an accusing fingers at whoever is on the dock in a trial of conscience.

Maqsoodul Haque is a popular singer and composer who steadfastly maintains his belief in creative freedom, including the freedom to reinterpret and reinvent traditional forms and genres of music.

Known as a nonconformist and something of a maverick, he is naturally not welcome in establishments where any deviation from tradition is considered a sin. Yet Haque has persisted, and, in the process, allowed his audience to rethink many old notions and review many entrenched attitudes. As for his poems: these too were often considered too strong for the taste of literary editors, and he found himself censored out of literary journals and newspaper literature pages.

As he he writes, in the ‘Notes to ‘Bangladesh 95: 176 years behind the world’…over the years, my notoriety and impropriety grew to be a cause of discomfort with the evolving ‘Media Mafia’ and I resigned to my fate on the Internet. It was good that Haque kept up his engagement with the Internet he at least found a space, which would not box him in. In any case, the Internet is a vastly more visited space than a printed English language literary page.

Despite the cold shoulder from the ‘Media Mafia’ he not only kept writing his poems, but upped his attacking tone while paying close attention to the demands of poetry.

In some of his poems, such as ‘Limits of Our Limitation, Bangladesh ’07, Polls 01,—’Political Atheism’ and a question of faith: A Prosaical Poesy and ‘Communiqué’ Haque’s attacks are merciless, since his targets are beyond forgiveness. ‘Our Press, Police and Politicians’, he writes in Limits of Our Limitations ‘have prostituted Public perception/ leaving us hapless and bare/ to a culture of despair.’

Haque is mortified and angered when people substitute truth for a bunch of lies which, when endlessly represented, assume the status of truth. Lies and half-truths thus form the basis of public discourse, and he says in utter despair in When LIES form the basis of TRUTH’-after all does anyone really care or give a damn when LIES form the basis of all TRUTH

Elsewhere he laments, The disease of denying and lying continues unabated. And when the disease spreads to the media and corruption becomes rampant, who can—or has the courage-to bring anyone from the Media to the book: ‘has anyone heard of demands/ to try anyone for media corruption?’ he asks.

On 11 January 2007, a Caretaker government took oath of office in Bangladesh, pledging to end corrupt politics and indeed, the endemic corruption that had catapulted the country to the top of Transparency International’s list of the most corrupt nations on earth. After some early moves and measures to tame, corruption and bring rogue politicians to justice, many of those who ran the government and supported it from behind the scene themselves caved in to corruption. Haque has written a piece, ‘Bangladesh 07 that records his soulful and angry outbursts. ‘Bangladesh in Two Thousand and Seven’, he says, ‘is a diseased corpse’, and goes on to diagnose the disease that has dispatched it from the land of the living.

In some other poems though, where Haque seems to attack people and places that are closer to him he proves that hatred and love are but two sides of the same coin. One good example of this double bind is ‘Dhaka: Ode to Aluminium Love It, Live It or Leave It’ where, after painting the city dead or nearly dead, he writes in the ‘Notes’ [which in this poem, as in other poems where they occur, are an integral part of the poem] In any case, there is no city in the world / would rather be-than Dhaka. He doesn’t want to leave Dhaka for a more functional, friendly and livable city: his ties of love with the city are simply too strong. In equal measure, his hatred for kitsch and Pettiness comes through in the poem, where he jeeringly dismisses the new fetish for the shiny metal and equates it with Dhaka’s love for ‘playing to and pleasing the gallery.

Haque seems to tone down his voice and become more introspective in his autobiographical poems.

There are two birthday poems, which lay bare a conflicting array of emotions happiness, regret, distress, ennui and indifference. As he considers his past and future and sees not much to be optimistic about, he is nevertheless intrigued by the numbers 47 and 51. It is indeed a bit strange that the poet celebrates these odd-numbered birthdays [50 is fine, or 40 or even 45, but 47?], but we quickly realize that what for most would be considered ‘normal’ or ‘usual’ may not hold much charm for him. He often sees in tradition both a smug acceptance of stasis and an indifference to change. This is precisely the mindset he would like to change.

In the end it is love, poetry and music that appear to rescue Haque from despair and give him the energy to drive forward, and the vision to construct an alternative future one which will be ‘butterly beautiful’ and where the ills of our age will disappear.

Although he laments that the ‘greal gOD’ singles poets out/ for slaughter of hearts’ he realize that this slaughter is part of the process of regeneration. Fo poets never die or disappear, they are born in every age to steer people towards love and music. Music, like poetry, is gift that gives life to the world.

As Haque ruminates for the day we kill Music will also be the day we ought to kill earthworms No, we can’t kill earthworms, nor can we kill music. The Bangladesh Poet of Impropriety is a testimony to the fact that whatever anger or rancour a poet might have against the ills of his age, he finds an answer to them not in ‘decapitation’ but in spreading the message of love and music.

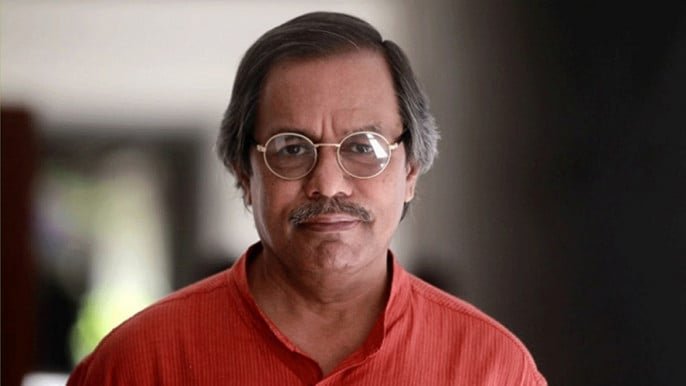

Professor Syed Manzoorul Islam

Department of English, University of Dhaka

January, 2010

[In 2010 my first (and only) book of English poems ‘The Bangladesh Poet of Impropriety’ was published and it was a sheer honour for me that the foreword was written by none other than my most respected teacher from Department of English, Dhaka University—Professor Syed Manzoorul Islam (SMI Sir for us) who made his transition yesterday. The following is what he wrote about me and my poems—Maqsoodul Haque, Toronto, Ontario 11th October 2025]

মাকসুদুল হক রচনারাশি

গানপারে সৈয়দ মনজুরুল ইসলাম

- FOREWORD: The Bangladesh Poet of Impropriety || Syed Manzoorul Islam - October 12, 2025

- শ্রদ্ধাঞ্জলি : বিভুরঞ্জন সরকার || মাকসুদুল হক - August 23, 2025

- Take a break folks and read this book - April 7, 2025

COMMENTS