1.

Not long ago, while putting together readings for a class, I found myself returning, yet again, to Karl Polanyi. The lecture concerned the expansion of market imperatives into nearly every sphere of life, and the transformation of our modern mode of existence that followed. Polanyi was one of the thinkers who first introduced me to the rise of market society, not merely as an economic development, but as a profound reorganisation of social life.

When I first read The Great Transformation, the encounter stayed with me. I wanted my students to grasp, perhaps even uncomfortably, what market society and its logic entail. For that reason, his text felt like the most honest place to begin, especially when introducing ideas about liberalism that must grapple with the age-old logic of laissez-faire and the self-regulating market.

By the end of the course, not without unsettling certain assumptions, I try to nudge my students toward a difficult conclusion: from a Marxian perspective, there is no deep analytical rupture between so-called Shahbag and Shapla, between “progressives” and “conservatives,” between “liberals” and “mollahs,” between the Awami League and the BNP, or any other formal opposition that presents itself as historically decisive.

From this, a question follows. Does our insistence on sides in these matters, or in any matter at all, prevent us from interrogating the social mediation that renders such sides historically necessary? And in doing so, do we leave the larger questions of freedom and emancipation largely unexamined in the realities of the twenty-first century?

By this, I do not mean that these formations are identical in policy, morality, or degree of repression. The differences are real. Rather, I argue that these binaries are historically constituted forms through which a shared mode of social mediation reproduces itself. Within this mediation, freedom is organised around exchange, productivity, and developmental time. In that sense, their antagonisms, however irreconcilable they may appear, unfold within the operative logic of a quasi-autonomous dynamic. Even when framed in the language of emancipation, they tend to intensify that dynamic rather than disrupt it.

Without recognising this, our claims to freedom risk illusion.

Of course, being a Marxist comes with its own penalties. In a disenchanted sense, it drains much of the pleasure from passionate commentary and makes everyday political life feel oddly deflated. Yet if our antagonisms are shaped by the very structures they claim to oppose, what would remain of our personal-political passions were we to suspend the binaries that give them emotional force?

I will return to this at the end of my rambling reflection on freedom and the unencumbered self, with a provisional sketch of the modern individual’s operational logic and the refined mediocrity it engenders.

This is hardly a coherent exposition of all the themes I am about to unfold. It is, rather, a stream of thought — a glimpse into the intellectual brain-rot I am trying to disentangle through writing. What is at stake here is the specific form freedom assumes under capitalist modernity. Within capital’s abstract, self-mediating dynamic, freedom is not eliminated but reorganised: it produces the unencumbered self, loosens durable attachments, and thins the moral substance of autonomy. The result is what I call refined mediocrity — not ignorance, but a pragmatic intelligence shaped by market rationality. This mode of consciousness preserves the experience of choice while quietly displacing obligation and leaving conscience unmoored.

2.

Somewhere in the middle of rereading Polanyi for the lecture I mentioned, a quiet realisation set in: I should stop pretending to have the firmest grasp of liberalism in the room, especially while claiming, however loosely, to be a student of Marx. With that recognition came a simple decision. It was time to call in the big guns: one of my Marxist professors, whom I invited to deliver the lecture himself.

The invitation wasn’t a casual choice. He has long been a beacon of political-economic thinking for me — a genuine senior comrade in a world already structured by the very liberal logic I was preparing to dissect. As a seasoned economist, I knew he could unpack the liberal funda far more rigorously, and far less sentimentally, than I ever could.

This requires some explanation.

The decision to call in a Marxist economist had everything to do with how I approach liberalism. I understand it less as a bundle of ethical commitments than as a historically specific political-economic configuration consolidated in the nineteenth century. These formations extended far beyond Western institutions and lifeworlds. Expanding alongside the globalisation of the capitalist market, they permeated not only political and economic institutions but also the intimate spaces of everyday life across Western and non-Western settings. In doing so, these formations reorganised how individuals think, evaluate, and situate themselves within the historically specific totality of capitalist modernity.

There are, of course, debates about whether liberal logics were institutionalised differently in coloniser and colonised contexts, or whether they diffused outward from the West while colonised societies merely adapted their vocabulary. But the problem cannot be reduced to diffusion, nor to differentiated institutional forms alone.

Capitalist modernity, as I understand it, does not merely travel. It restructures the very conditions under which social life becomes intelligible. Its logic operates in a universal register, irrespective of provenance.

This universalising dynamic finds a clear historical articulation in Andrew Sartori’s Liberalism in Empire: An Alternative History. If freedom constitutes liberalism’s foundational analytical category, Sartori’s study of agrarian Bengali Muslims’ conceptions of freedom in the decades preceding Partition demonstrates how that category was articulated beyond its presumed Western origins. In the first half of the twentieth century, within the Bengal hinterland, one encounters a distinctly Lockean grammar of freedom precisely where liberalism was presumed absent. Sartori shows that this articulation of freedom was neither mimicry nor passive reception, but a mediated enunciation arising from the social forms of capitalist modernity itself.

Seen in this light, the reach of that logic is not simply wide; it is constitutive. It operates in governance and political theory, but also in aesthetic sensibilities and everyday practices of the self. Liberalism does not merely organise institutions; it reorganises the categories through which we reason, desire, and justify ourselves. It reshapes the moral and social universe we inhabit, often without announcing itself, even in forms that present themselves as its negation.

All of this explains why I felt compelled to invite my economics professor in the first place. Liberalism, in this light, is neither simply politics nor merely ideology, nor even “the economy” taken in isolation. It is a historically specific organisation of social mediation grounded in capitalist relations of production. As my professor has repeatedly emphasised, political economy is ultimately the study of those relations.

Who else, then, was I supposed to call upon other than a Marxian economist?

3.

In any case, not to linger too long on my admittedly inadequate understanding of liberalism, my professor agreed to deliver the lecture, though not without his familiar playful provocation. Polanyi, he insisted, is not really up to the mark when it comes to understanding liberalism. Were he in my place, he said, he would rather teach Maurice Dobb or Paul Sweezy — thinkers he described, confidently, as “Marxist to the core.” My fondness for Polanyi, by contrast, apparently revealed me to be nothing more than a bare left-liberal.

In a strange way, the remark felt like tasting my own medicine. Anyone who has had an intimate and frank exchange with me about political economy would have noticed, perhaps with some irritation, my tendency to label others as “thoughtless liberals”.

Yet being called a left-liberal in that context did not trouble me much. My peers might disagree, perhaps indulgently, but I have always tried not to be intolerant of analytical depth, especially when it comes from someone who genuinely knows how and what to think, regardless of ideological location.

What I struggle with is not disagreement. It is a certain performative mediocrity: narcissistic, self-assured, draped in the language of tolerance and pragmatism. My professor does not belong to that category, which is precisely why I respect him. Better an honest adversary than a polished evasion masquerading as openness.

For that reason, I have remained indebted to him for years of such disagreements, especially in a world increasingly shaped by refined mediocrity and by the NGO-isation of liberalism, with its depoliticised and hollowed notions of freedom.

But then again, why would two Marxists ever agree on anything when they could spend a lifetime arguing over analytical detail?

4.

That midday exchange lingered. In the slightly hazy hours that followed, I found myself trying to process what exactly it is about Polanyi that keeps drawing me back. It was not that my professor was wrong in his sharp observation that Polanyi does not remain faithful to a strict Marxian method. Nor, admittedly, does one get called a left-liberal every day.

Later that evening, once I was back home, the conversation pushed me toward a more basic question. In fact, this is the real reason I am writing this half-analytical, half-gibberish, mostly biographical jabberwocky. The question hovering in my mind was simple: why does Polanyi hold my attention so persistently?

It is not because my Marxian training is nonexistent, nor because I am unfamiliar with Lukács or the Postonian reinterpretation of Marx. Dobb and Sweezy are formidable Marxist economic historians. Polanyi is not one of them.

And yet, without hesitation, I can say that few thinkers have compelled me to think as seriously about liberalism as Polanyi has. He may not offer a systematic account of the transition from feudalism to capitalism. But once one begins probing the institutional and moral foundations of market society, his insights become remarkably difficult to bypass.

Moreover, his critique is not merely structural or economic. It probes the conditions under which individuals in a market society come to think, desire, choose and gradually accept a shrinking horizon of what constitutes meaning. It forces us to ask: why do we like what we like? What does that reveal about choice itself? At what point do our preferences begin to feel natural because they are no longer fully ours?

Perhaps this is my aesthetic, rather than strictly analytical, reading of Polanyi — the reading of someone unsettled by the cultivated mediocrity and detachment I mentioned earlier. In such an age, even our sense of what we ought and ought not to do is shaped by the liberal ideal of the unencumbered self. I cannot elaborate fully here on what that means, though those interested may turn to Michael Sandel for clarification.

Polanyi, however, never explicitly theorises this “unencumbered self,” yet his critique of market individualism gestures toward a different moral imagination, one opposed to a hollowed-out self attached to nothing and bowing before nothing. Is this not the very figure idealised by market logic as it took root so decisively in the nineteenth century?

Following that line of thought, it becomes difficult not to recognise that even our most cherished notions of freedom and free will are already mediated by the logic of the self-regulating market within capitalist modernity. If that is so, then the question Polanyi repeatedly circles, albeit implicitly, is whether meaning can still reside in a society where liberalism sinks its roots so deeply into both political and individual life.

It is this insistence that sets Polanyi apart from many who have written on the rise of market society and the consolidation of laissez-faire doctrine. His work carries a distinctly anthropological undertone, attentive to the ways economic arrangements are embedded in moral and social relations. That sensibility perhaps explains why his engagement with Christian socialism initially caught me off guard. I had not fully registered how deeply his critique of Economic Man was intertwined with a moral vision. Yet once encountered, that dimension of his thought felt less like a surprise than a clarification.

After all, if one is serious (and honest) about confronting the difficulties of the modern individual, what alternative remains but the search for a different moral imagination?

Surely, liberalism is not the answer, neither in the so-called “Shahbagi” aesthetic lifeworld nor in the stylised “illiberal” vocabulary of Shapla. Both logics, despite their apparent opposition, draw from the same underlying contradiction within liberal political economy. Strip away the ideological surface and move toward the structural core, and what becomes visible is not two irreconcilable camps but two polemical expressions rooted in the internal contradictions of liberalism’s own viability.

5.

It is often in moments of acute political crisis that alignments between otherwise antagonistic formations become historically legible. The mass uprising of 2024 marked one such moment. Actors across the ideological spectrum — centre, left, and right — converged around a shared normative language shaped by liberal demands for merit and freedom. What appeared contingent was articulated within a determinate liberal grammar. Crisis rendered visible the structured coherence of the liberal political-economic form within which antagonism unfolds.

This convergence did not dissolve ideological differences. It disclosed that divergent ideologies operate within a shared political-economic structure constituted by liberal forms of social mediation: labour mediated through the market, entitlement through property, and collective aspiration oriented toward developmental time. In opposing a neoliberal regime, appeals to merit and freedom assumed the form of immanent critique within that structure: merit as the claim that reward corresponds to labour only insofar as it assumes the form of abstract, socially validated value; and freedom as the experience of autonomy within relations governed by impersonal market imperatives.

The uprising therefore did not repudiate liberal categories, nor did it confront a regime external to liberalism’s horizon. It emerged amid neoliberal restructuring that intensified the market mediation of labour and exposed the disjunction between labour as concrete effort and labour as abstract, value-generating activity. As entitlement became increasingly organised by the imperatives of valorization rather than lived work, appeals to merit and freedom registered tensions generated from within liberalism’s internal logic.

A comparable configuration was evident during the 2007–2008 Singur–Nandigram movements in West Bengal, where formations from the disaffected left and the populist right aligned against the Left Front government. Their contestation, centred on property rights, produced a temporary convergence in which property functioned as the organising category. What became visible was the persistence of the same liberal political-economic horizon structured by property as a foundational form of mediation. It is this horizon — rather than the contingent alignment or surface antagonism — that warrants scrutiny in both the 2024 uprising and Singur–Nandigram.

By extension, this horizon also structures our modes of thought. Once we move beyond the apparent autonomy of political antagonism, the binaries invoked at the outset — Shahbag and Shapla, “progressives” and “conservatives,” “liberals” and “mollahs,” the Awami League and the BNP — appear less as external oppositions than as determinate positions within the same mediating structure. What surfaces in political rhetoric as stark opposition can thus be understood as the expression of contradiction internal to liberalism’s political-economic form. I cannot pursue this tension fully here. Still, the present moment invites renewed inquiry within the analytical framework developed in Liberalism in Empire, where such tensions are shown to be historically immanent to the social life of liberal categories.

Even without pursuing that analysis, one point should be clear: these contradictions cannot be reduced to the affective grammar of political binaries through which contemporary antagonisms are typically apprehended. To remain at that level would confine the question of freedom within the very framework under scrutiny.

It is therefore necessary to approach the problem from another vantage point — that of the individual subject.

6.

If this is the predicament of freedom as constituted under capitalist mediation, then freedom is no longer merely a political-economic question. It is here that literature begins to register what theory can only schematise. Critical political economy can analyse the historically specific forms of abstraction through which social life is mediated; it cannot render their lived texture — the erosion of meaning and the burden of agency within the impersonal structures of capitalist modernity.

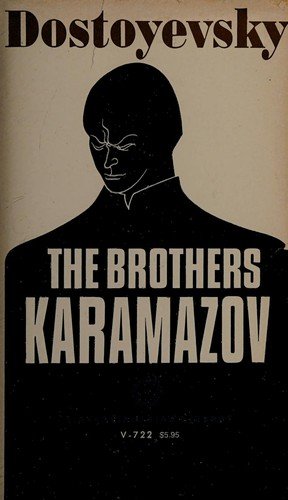

It was in this spirit that I found myself turning, recently, to The Brothers Karamazov, not as an escape into fiction, but as an inquiry into a world in which freedom has been severed from transcendental foundations.

I invoke Dostoevsky here because my inquiry concerns the problem of the unencumbered self and the specific form of freedom that liberalism so confidently celebrates. Dostoevsky, one of the greatest novelists of the nineteenth century, had already staged this crisis in The Brothers Karamazov. His concern, however, was more existential: the encounter between Enlightenment rationalism and Eastern Orthodox spirituality, between the sovereignty of reason and the submission of faith. For him, religion was not a reactionary refuge but a site at which conscience either sustained itself or gave way.

It is in Ivan that this tension between reason and faith takes its most acute form. As the rationalist Enlightenment figure who rejects consolation, he represents both the dignity and the danger of autonomy. His trajectory remains ambiguous, yet unmistakably tragic. Was Dostoevsky suggesting that a subject severed from transcendence cannot sustain conscience without collapse beneath the very autonomy it claims? Ivan does not merely doubt; he unravels.

In that light, the Karamazov brothers are not mouthpieces for doctrines but trials of conscience. In a characteristically Dostoevskian manner, none of them — Dmitri, Ivan, or Alyosha — is granted the comfort of moral clarity. Dostoevsky refuses resolution. Why wouldn’t he? To write honestly about the modern individual is to expose the strain of acting under the burden of one’s own freedom in a world where metaphysical assurances no longer hold.

The crisis this example exposes is simple: many contemporary freethinkers and self-styled liberals never even arrive at Ivan’s ordeal. It is hardly surprising, since what guides their reasoning if not the market that sets its limits of conscience? More often than not, their instrumental and pragmatic logic resembles that of the fourth, half-acknowledged Karamazov, Smerdyakov: efficient, compliant, and quietly obedient to the impersonal order that structures their freedom and silently defines their horizon of emancipation.

My point, however, is not to reduce society to literary archetypes. Rather, the novel clarifies, in resonance with Polanyi, that for over a century thinkers have been circling the same problem: the operational logic of the modern individual.

As Moishe Postone has argued, capitalist modernity produces formally free individuals who are nonetheless constituted through abstract structures of value and time. The subject appears autonomous, yet its very capacity for action is mediated by forms of social mediation that operate as objective constraints. What presents itself as self-determination is, in fact, the internalisation of systemic necessity: domination rendered reflexive, compulsion experienced as choice. Freedom, under such conditions, is not abolished; it is reorganised. In that reorganisation, the modern individual inhabits a paradoxical condition — formally free and morally self-authorising, yet constituted through the imperatives of capital’s temporally driven dynamic.

Read together, the problem sharpens. We are released from the transcendental foundations of Enlightenment and religion, yet reconstituted within the abstract logic of capital that hollows out meaning. The real dilemma, then, is not whether we are free, but what kind of freedom we inhabit — and whether it binds conscience to anything durable.

And so the question returns with greater urgency: if neither religion nor Enlightenment offers stable ground in a liberal society like ours, what remains when the logic of capital saturates the individual, the social, and the political alike? This logic operates as abstract domination, even when it presents itself ideologically in the normative language of laissez-faire liberalism.

What form of conscience can endure when freedom itself is mediated by exchange — when even art, love, politics, and music operate within the grammar of value?

7.

My conclusion does not imply a rejection of critique, whether liberal or Marxian. Critique remains indispensable. Yet in a world as chaotic as ours, it cannot serve as the final resting place. What increasingly troubles me is the possibility that the spread of refined liberal mediocrity is not a failure of intelligence at all, but a defence mechanism against an eroded sense of conscience. Its limitation lies not in incapacity, but in an inability to become reflexive about the unfreedom in which it is ensnared.

At the centre of this unfreedom lies a concealed structural dynamic. It binds the subject and silently reorganises the very conditions of agency. What emerges is a polished autonomy — one that encloses the individual within the self and recasts identity as consumption. In time, even the humane and the transcendental are appropriated and reconfigured within the grammar of abstract domination.

Under such conditions, the ideal individual is the unencumbered subject bound to self-interested rationality. Commitment collapses into preference; belonging hardens into transaction. At this edge, individuality binds itself to nothing beyond forms engineered to intensify pleasure while sustaining a market-scripted coherence. In their various innovative guises, these forms — whether ideas or commodities — may be presented as dissent or absorbed into conformity.

If that is indeed the case, then the problem is no longer merely how to think more rigorously as critics of such liberal mediocrity, with all its gimmicks and self-assured hyper-individualism. The deeper question is whether anything remains that still obliges our conscience to think, or to care, at all.

These implications are more unsettling than I had anticipated. For good reason, they have led me to reconsider the role of religion, not as dogma or reaction, but as a medium: one that once situated the individual within a horizon larger than instrumental rationality, a horizon whose erosion now demands renewed reflection.

And with Enlightenment confidence diminished and God absent, what alternative horizons, other than religion, remain for those who seek to resist the disintegration of community?

…

- By “thoughtless liberals,” I mean those prone to intellectual shortcuts who hide behind the language of “pragmatism,” or, among the artistically inclined, behind a posture of “aesthetic quietism,” to define what is feasible and present it as innovation. What passes for this kind of gimmick realism is often nothing more than the internalisation of what the market and liberal thought already permit. I do not see this as novelty of any kind, but as a refusal to pursue an understanding of reality to its uncomfortable conclusions—conclusions that resist compromise with class-blind, uncritical ideologies animated by jingoistic passion.

- To me, refined mediocrity is not ignorance. It is the adaptation of intelligence to the limits of market rationality. It is competence without transcendence; critique without rupture; autonomy without risk.

- A case could be made that Alyosha is granted a form of moral resolution, but such a reading would remain far from uncontested.

- My point of divergence from Dostoevsky lies in his apparent opposition between Enlightenment and religion. I regard both as grounded in transcendental claims, albeit of different kinds, and my own inclination remains with the autonomy of human reason and logical inquiry. At the same time, Enlightenment rationality and liberal market logic are not identical formations; the latter cannot simply be reduced to the former.

Author’s note: Though terms such as “refined mediocrity” and “thoughtless liberal” risk discourtesy, I have found no alternative formulations that adequately capture the phenomenon I am attempting to describe from lived experience. If their tone sits uneasily within the larger reflection, that tension is not entirely accidental.

Read more by Shafiul Aziz

gaanpaar English originals

- Refined Freedom, Eroded Conscience || Shafiul Aziz - February 21, 2026

- Quiet Allegiance to Science || Shafiul Joy - March 21, 2025

- বসু ও দত্ত || শফিউল জয় - March 18, 2025

COMMENTS